FTR’s current forecast for truck loadings is essentially running flat. That could be revised downward to small negative numbers.

Source: FTR

Although there is still a great degree of uncertainty about what 2023 will bring in trucking business conditions, analysts at FTR believe a major recession is unlikely.

FTR’s “State of Freight” webinar on Jan. 12 explored the economic indicators that most affect the freight market as well as trucking-specific numbers and offered FTR’s outlook for the year.

Key Takeaways on the State of Freight:

What’s the Health of the Economy?

Avery Vise, VP, Trucking, said the theme of the webinar was uncertainty, “and that is all about the economy.”

Inflation is a big factor on everyone’s mind. The good news is that the latest inflation numbers showed inflation was cooling, slowing for the sixth straight month in December.

The Consumer Price Index, a measurement of what consumers pay for goods and services, skyrocketed in June to 9.1% but has been falling since, with the federal government raising interest rates to cool the overheated economy. December numbers show the CPI rose 6.5% in December from a year earlier, which was down from 7.1% in November. If you exclude volatile energy and food prices, the Core CPI climbed 5.7% in December from a year earlier, down from a 6% increase in November.

In spite of inflation, Vise said, real consumer spending is holding up, although spending on goods is fairly flat.

Imports mean more freight for trucks to move, so the drop in incoming intermodal containers is a concern.

Source: FTR

In addition, he said, “we are seeing payroll job growth slowed but still solid. In this high inflation environment, that’s a positive sign,” because it’s believed that rapid job growth can contribute to inflation.

Asked about the likelihood of a recession, Vise explained that what determines a recession is not as simple as the widely cited metric of two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth.

“We kind of have to redefine what a recession is,” he said. A lot of the negative GDP numbers earlier this year related to imports rather than the overall economy.

“And we’re still seeing solid job growth,” he said. “I would say we’re in a slow growth environment. We’re not likely to be in anything we would consider a recession for the next couple of quarters, and even then, it’s unlikely to be anything more than mild.”

How Economic Indicators Affect Demand for Goods Transport

Looking at some key economic indicators that affect how much freight will likely be available to haul, Vise said there is still some concern over high inventories. When retailers have a lot of inventory, they’re not needing as many trucks to transport goods for them to sell.

Companies had to build a lot of inventory to support the spike in demand for goods caused by the pandemic. With inventories still higher than the pre-pandemic trend line, he said, “it raises concern, as we expect consumption to fall off over the next two or three quarters.”

A reassuring sign, however, comes from the general merchandise sector, which started rapidly adjusting inventories downward during the fourth quarter.

Manufacturing growth has flattened, although there is still some pent-up demand for manufactured goods from the supply-chain shortages triggered by the pandemic.

The industrial production outlook for 2023 is essentially flat.

Looking at GDP, Vise said, FTR expects the fourth quarter numbers when they come in to be “quite strong relative to the second and third quarters and perhaps relative to peoples’ expectations.” However, FTR’s forecast does call for it to slow quite a bit in 2023.

“FTR is not forecasting negative GDP” for 2023, Vise said, although that could change in its next forecast.

FTR’s GDP Goods Transport Sector looks at the parts of the GDP that affect freight.

Source: FTR

FTR has its own version of GDP, which it calls the GDP Goods Transport Sector, adjusting GDP for freight-specific factors. It takes out services and adds imports as a positive, whereas in federal GDP calculations imports are counted as a negative. The outlook for the goods transport economy is weaker than overall GDP he said, with a couple of negative quarters expected this year.

“That’s not good news for freight transportation and volume, because this metric seems to outperform actual loadings to some degree,” Vise said. “That’s probably going to translate into a negative environment.”

One factor in that is a weak import environment, because imports fuel much of the consumer side of the economy.

Freight Rates and Capacity

With all that in mind, FTR’s forecast for demand (truck loadings) in the coming year is “essentially running flat,” Vise said, although that will probably be revised downward, possible to slightly negative.

So what about the capacity side of the supply-demand equation?

Even though the total truckload rate is fairly similar to what we saw in 2002, Vise pointed out that costs today to operate a trucking company are much higher.

Source: FTR

Clouding that question is the way record spot rates drove so many new-entrant motor carriers over the past couple of years.

“The thing that has really popped out is what has changed in the carrier population base,” Vise said. “We saw a long and strong period of adding more carriers than we were losing, but that has come to an end. Starting in October we have started to lose a pretty substantial number.” Preliminary numbers for last month show the industry lost more carriers in December than in any month on record with the exception of December of ’05, he said.

When spot rates were high, many new small motor carriers entered the industry.

Source: FTR

But, this does not necessarily equate to what happens to capacity. The reason for the huge swell in new motor carriers was primarily owner-operators getting their own authority and riding on record high spot rates. When spot rates weakened and fuel prices spiked last spring, a lot of those companies couldn’t make it.

“Clearly a lot of those drivers were absorbed into larger carriers and we saw a shift of capacity from the spot market to the contract market,” Vise said.

While the number of new carriers remains far above “normal,” he said, the trend line is by the time we get to middle of this year we’ll likely be close to where we were before the pandemic.

But with payroll employment in trucking currently appearing to be peaking, he said, many of those drivers probably won’t be absorbed into the employee-driver population.

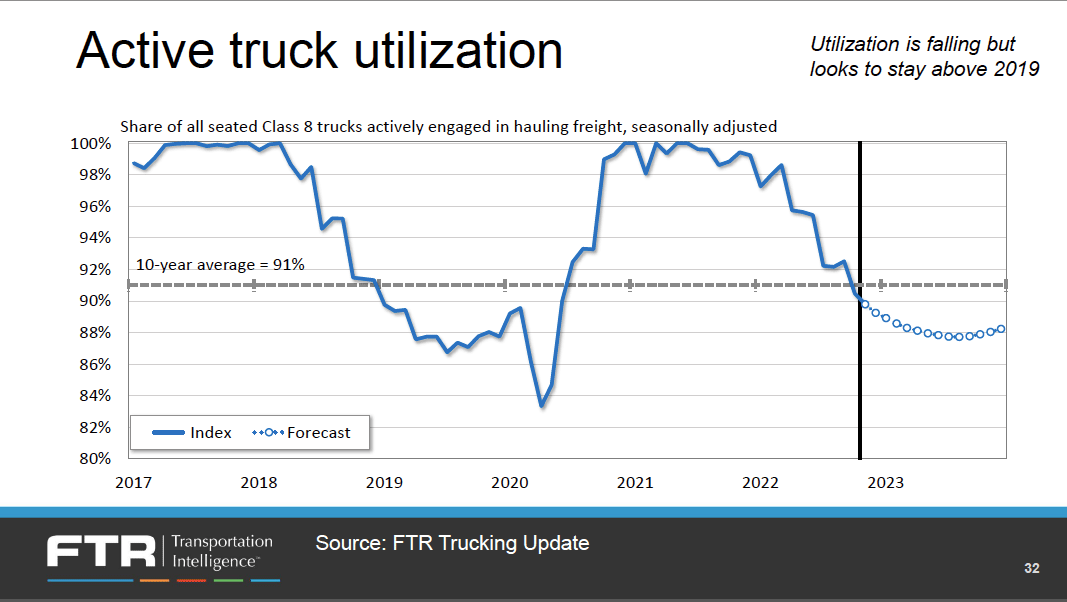

FTR’s utilization numbers, an indication of capacity, are falling. In 2021 and into 2022 there were months of near full utilization, but it started falling in 2022 and likely bottomed out in the third quarter, Vise said.

FTR’s truck utilzation number shows we’re no longer seeing the tight capacity that has kept rates high.

Source: FTR

Lower utilization means more capacity and lower truckload rates. “Spot rates likely are close to bottoming out,” Vise said. “We are in an environment where overall freight levels are not likely to change a whole lot over the year.”

Asked about why we still hear talk of a driver shortage in light of this capacity shift, Vise said, “I believe what a lot of people call a driver shortage is, frankly, just the churn that’s always there. There’s significant [driver] turnover, even during a downturn.”