Truck makers and suppliers have done their part and created more efficient and zero-emission powertrain technologies. But fleets need real help now to implement them.

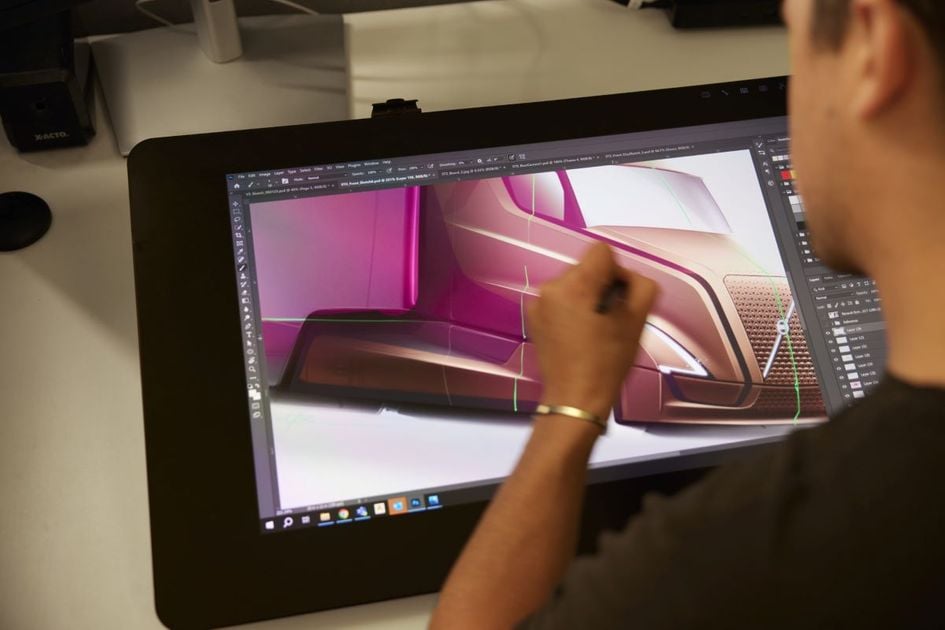

Photo: Volvo Trucks North America

The American Trucking Associations’ Technology & Maintenance Council has always been a source of important insights into the health and confidence of trucking in North America. But as TMC’s 2024 Annual Meeting wrapped up in New Orleans, I drove away from the Big Easy with a sense that the industry is nowhere near ready for new emissions regulations that start kicking in for the 2027 model year.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s rules on NOx (Nitrogen Oxides) reduction mandates were published in late 2022.

Just weeks after TMC, EPA finally finalized its Phase 3 greenhouse gas emissions rules, which the agency says are designed to complement the NOx reduction standards. While the EPA says it is not telling truck makers how to meet its CO2 limits, it clearly intends for trucking to begin transitioning to zero-emissions vehicles.

Both of these new emissions standards mean that fleets looking to buy trucks are going to have to decide whether to look at some form of propulsion other than diesel or take a chance on diesel trucks equipped with new emissions-reduction technologies.

An Industry in Paralysis

It was hard to escape a feeling of paralysis at TMC, a feeling that a tsunami of change is rushing at all of us.

The fact is that the vast majority of North American fleets are nowhere near ready to transition to zero-emissions vehicles. And for most of them, the technology isn’t even ready yet.

Yes, truck OEMs have done an incredible job developing battery-electric trucks. And the first hydrogen fuel cell models are starting to enter the market. But these trucks are vastly more expensive to purchase than diesel trucks. So is installing private charging or fueling stations. And public infrastructure is virtually nonexistent.

And while those trucks will work well in short- and regional-haul applications, a massive question mark hangs over when we’ll see trucks that can perform as well as diesel trucks do in long-haul applications.

Which is why a massive diesel truck presale will spark off soon — later this year, most likely. Too many fleets were burned by the round of emissions cuts in the 2000s, where regulations forced low-emission engines to market before they were truly ready, leading to maintenance headaches aplenty.

Many fleet managers are going to look to go ahead and buy the trucks they’re already familiar with, causing a white-hot heavy truck market that will burn hot and fast until January 2027, when truck sales will fall off a cliff.

In the aftermath of the prebuy, fleets will squeeze every last mile possible out of their pre-2027 model trucks. And they’ll watch the truck markets carefully to see if ZEV prices fall, infrastructure develops or new fuels or powertrain technologies emerge that will help them eventually ease into zero-emission vehicles. But it could be several years before that happens.

Fleets Need Real Help in Understanding the Impact of New Truck Emissions Rules

I’ve been fretting about this situation for months now. And walking TMC this year, I got the feeling I’m not the only one.

Simply figuring out what they’re going to have to do, what vehicles are going to be available to them, how much it’s going to cost, is a tall order for fleet managers. Just try reading through the EPA’s 1,155-page final rule on GHG Phase 3. And truck makers have different paths they can take to meet the emissions standards, including using “credits” to offset trucks that don’t meet the cut-off by selling ones that exceed the standards.

Our entire economy is literally riding on getting this massive transformation to zero-emission vehicles right.

Expecting diesel engine manufacturers and North American fleets to shoulder the cost, installation, transition and deployment of new technology of this magnitude is not a sober, reasonable, and well-thought-out solution to this problem.

The costs of pulling this transformation off — even for big fleets — are astronomical. The industry leaders in BEV adoption will tell you they can’t do it without government financial help.

And medium-sized and small fleets? The costs are going to be prohibitively expensive. Many of them will simply throw up their hands and walk away from the industry entirely. And who can blame them?

We Need Another Moonshot

Let me be blunt here: We — as a country — are not taking this transition to clean energy seriously.

If we were, you’d see billions of dollars being pouring into high-speed and light rail. You’d see serious work being done on building natural gas and hydrogen fueling stations and electric charging infrastructure. We’d be mandating renewable diesel nationwide. We’d be building charge-enabled electric truck lanes. We’d be pouring money into new power stations, windmills, tidal power generaton plants and even nuclear power plants.

And, most crucially of all, we’d be setting up meaningful and effective national grants and incentive programs to OEMs and commercial fleets of all sizes to help them quickly acquire, evaluate and deploy zero-emissions vehicles now.

But, instead, the rest of the country is sitting back looking at the trucking industry, and expecting it to save the world all by itself.

That’s not going to happen.

Now, I’m not naïve. I understand that I’m proposing a massive government program on par with the Apollo Program or the Manhattan Project. And that’s exactly my point: We’re talking about transitioning a critical component of our economy to completely new technologies.

There is no question that such a massive, and crucial effort should be given the same priorities and funding levels that put men on the Moon and developed the atomic bomb. The size, scope and scale of what is being proposed for the trucking industry is easily as big as those projects — and just as important for our continued economic and national security.

The trucking industry needs real, tangible and substantial help if it’s going to make this transition to green energy. And we’re all going to be in real trouble if it doesn’t get it soon.